Many writers have a great mystery centering around someone who was killed. The body is found, and that sets off the police investigation as to when the victim was last seen . . . and with whom . . . etc.

But . . . what if a body is never found? Can there be a murder if there is no body? And if a suspect is located, can they be charged with murder even though the body or “victim” can’t be found?

The answer is yes, a suspect can be charged with murder if the actual victim’s body is not yet, or ever found. Keep in mind that being “charged” with a crime does not mean there will ever be a trial for the crime charged.

Why?

The prosecutor or district attorney, after the suspect is charged, could later determine that there isn’t enough other evidence to warrant a trial where the suspect would be convicted. And conviction is the magic word with prosecutors and district attorneys, because if the case is weak, and the trial results in a “not guilty” the defendant cannot be put on trial again for the same charges. That is guaranteed under U.S. laws in the manner of “double jeopardy.”

Prosecutors and district attorneys only get “one bite out of the apple” in a criminal trial. Remember, when a suspect is first charged, they are not referred to as a “defendant” until later in the criminal justice system when they are indicted by a Grand Jury. These legal terms are covered in other posts on my website.

Of course, in cases where a body is not found and a suspect is charged with murder, you will read about the suspect’s defense attorney standing on the steps of the courthouse in front of the press microphones preaching that his or her client is innocent because the State has no body – thus no proof – that the victim was actually killed. This is not true. Just keep in mind the defense attorney is getting paid to defend their client, and just doing their job. A smart defense attorney will use the press to soapbox their client’s innocence, because they know that those watching him or her now may later on be called as jurors in the suspect’s trial . . . and might remember his or her press conferences.

So how does the State even have a chance at convicting a suspect without the body? After all, the body is THE most piece of evidence at a crime scene. It might have forensic evidence upon it, such as the suspect’s hair or blood, or fibers from the suspect’s clothing, skin from the suspect under the victim’s fingernails, stomach contents, or other transfer evidence. Also, the victim, once identified, will have their movements for the last 48 hours traced by the police, to ascertain who they were last seen with, where did they last go, what did they eat (stomach contents can determine approximate time of death), who were their friends and enemies, etc.

So, without all the victim’s actual body can offer the police, what else is left?

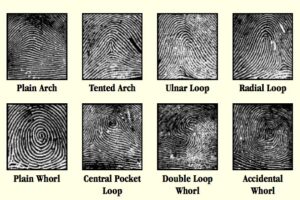

Just like the puzzle picture at the top of this blog, the police, with enough circumstantial evidence, have an excellent case without a body. If you look at the puzzle, even though one piece is missing, you still get the picture. It is the same in cases where the victim’s body has not yet, or ever, found. The body of the victim, the missing piece, does not hinder the police in seeing the bigger picture.

Circumstantial evidence, in many cases where a body is never found, can be more overwhelming and exhaustive than cases where a body is found. How can that be? Simply because in cases where the suspect has gone out of their way to hide or dispose of the body, they may have left a more detailed trail than if they had just left the body where it was killed. A trail such as buying bags at stores to dispose of the body; using towels to wipe off blood; wiping down walls from blood spatter; cutting out carpet where a victim’s blood was; calling or texting a co-conspirator; ditching the victim’s car; setting up alibis that are totally out of line with the suspect’s normal routine; hiding the murder weapon, or even staging the crime scene to make it appear the victim simply left on their own.

I investigated a case where the suspect wiped down the walls of the room where the murder occurred with bleach, then went out and bought new paint and painting equipment. He then disposed of all the paper towels, paint cans, painting equipment, etc. in a dumpster. He transported the body several counties in the carpeting from the floor of the room he committed the murder. He then returned and made sure all the garbage cans in the home were empty and had new garbage bags in them. Needless to say, the smell of fresh paint, bleach and empty garbage cans gave solid indicators that the missing victim had been killed, not just disappeared.

In today’s age of video surveillance cameras, civilian cellphone video, traveling on highways using toll records and cameras, cellphone and e-mail tracing, even Google Earth and satellite imagery, the police can piece together a better timeline of a suspect buying garbage bags, paint, bleach, painting equipment, and in general their movements before and after the crime than ever before.

So, a suspect, in an attempt to conceal the body from the police, ends up creating a series of actions and events, when coupled with forensic evidence, that although circumstantial, is overwhelming and easily used at a trial. The fact that the actual body is not part of the evidence at the trial will be a bone of contention that the defense attorney for the defendant will harp on, while the State will present the timeline of circumstantial evidence as part of their case.

In the end, although there are cases where there is no body found, as it is inscribed upon in Latin on the wall of the New York City Chief Medical Examiner’s Office “Hoc est ubi mortuus vivos auxilio” . . . which means “This is the place where the dead help the living.”

Sometimes, it is the suspect’s actions to conceal the body that help the dead.