When talking about “crime” not every culture has the same “type” of crime, or criminals. The exact types of crimes that are running rampant in other countries would not be the same as in the United States. Of course, the basic crime would be very similar, but culturally each country would have variations in crime, many times based on societal morals, or the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of the legal & justice system to solve and punish those found guilty. Remember, a “crime” is only a crime if there are laws prohibiting it. If there aren’t, commission of the act is not a crime. The act may be morally wrong, or frowned upon, but if there is no law against it, a person engaging in that behavior cannot be charged with a crime. And a crime is only considered that if you are convicted of it, you may be subject to incarceration. If you are sued for a million dollars, that is civil, and you can’t be incarcerated just on the lawsuit.

Stealing someone’s parking spot in a supermarket parking lot? Not a crime. Picking your nose in the office elevator? Not a crime. Not being a writer that has taken every step to be factual in their works? Not a crime! But . . . don’t do it . . .

The underlying roots of crime, criminal behavior and criminal motives are imperative in how crime is solved. Criminals are creatures of habit once they have honed their craft. It’s the old saying “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Let’s talk about you. You may be a great teacher, or bricklayer, or banker, mother, or salesperson. Over time, by trial and error, you will learn what tips and techniques make you better at your profession, and you stop doing what doesn’t improve your craft. You learn from your mistakes and successes. What criminals do is essentially the same thing. They will use what works for them (which means it keeps them from getting caught by the police) so as to allow them to continue their life of crime, whether it is murder, rape, robbery, bank robbery, etc.

NEWSFLASH! Contrary to what some crime “experts” espouse on television when they are interviewed about criminals leaving small clues behind on a local case, almost all criminals do not want to be caught by the police.

Child molesters can’t molest children in jail. Bank robbers can’t rob banks in jail. Arsonists can’t burn homes in jail. Drug dealers can’t deal drugs in jail. So, any clues left behind at a crime scene by a criminal are either because of poor planning & execution, inexperience, mental illness, or complacency.

Let’s jump right to a real-life scenario: For example, let’s imagine Johnny Kreep decides he wants to kidnap Molly, a cashier at the all-night convenience store in his town after her evening shift is over. His plan is to bind her, then take her in his car to his home and have his way with her. But he has a problem. Johnny has never kidnapped anyone before. So, he decides to snag Molly as she walks to her car in the parking lot of the 7-11. He brings thin twine with him to bind Molly’s hands. She breaks free, and calls the local police. Johnny Kreep gets arrested, charged and sentenced. During his stint in jail, he learns from his fellow inmates that he should have either knocked Molly out right away as soon as she entered her car; used very thick rope or duct tape to bind her; or perhaps made up a ruse to get her to his home. So, he refines his “method of attack”. Jail is literally a university of higher learning for inexperienced criminals to learn from those more experienced. So, that method of attack recommended by his jailhouse mentors, if it works the next time, will continue to be used by Johnny Kreep, which is good for the police, as it becomes his MO, or Modus Operandi, literally his “method of operation.” That’s what police look at, among many other things, in identifying a criminal at large.

“Victim selection” is the process or criteria a criminal uses to select a victim. This selection of a victim, and the type of victim, tells us a lot about the type of criminal police are looking for. Each offender has their own selection criteria which satisfies their own needs. A victim can be the whole reason for the crime, or a mere secondary casualty. For example, a sexual crime may be the basis for a criminal to acquire a certain type of victim (child or adult) and then refined even more (male or female) and even more refined, (such as a blonde, or redhead or brunette), then on and on and so forth as to race, height, age, weight, hair style.

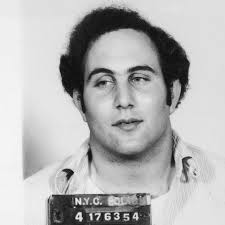

Serial killer David Berkowitz, for example, loved young women with long dark hair parted in the middle. When that became known based on the police investigation as it unfolded, hair salons in the boroughs of New York were swamped with young women with long hair parted in the middle seeking an immediate different hairstyle.

Here are some processes that a criminal goes through in their minds to commit a crime and the choices the criminal wrestles with:

LOCATION: Is the victim selected in an open area, or crowded area, perhaps dimly lit parking lot, or a crowded mall? Where they alone or with others? Did the offender use a ruse or some other method of trickery? Did he use brute force to overpower a victim? Were they walking on a street, or in an alleyway, or across a parking lot?

AVAILABILITY: How risky was it to attack the victim? For example, taking a child, no matter from where, is high risk from the offender’s point of view as children are easily and quickly missed. So a criminal taking a child is taking a tremendous risk. That tells us the offender is most likely sexually motivated in his endeavors. Most missing children are dead within 3 hours of their kidnapping. The child, in the criminal’s mind, is a witness that must be eliminated.

An example of a low risk victim, from the offender’s point of view, is a prostitute, or an over-the-road trucker, a homeless person, or a runaway. Nobody misses these classes of people as much, as they are used to being away from home for days or weeks or years at a time. So it will be a while for them to even be noticed as missing.

VULNERABILITY: This is how the offender perceives the victim. Children, elderly, women alone, etc. are seen as easy marks. However, many a robbery-motivated thief has been surprised when Granny chases after him and pounds his sorry derriere, or a woman alone overpowers the criminal and shoots him with his own gun.

In homicides, who the deceased is plays a critical role in catching the killer(s). Everyone has friends, enemies, and everything in between. Most victims somewhat know their offender, whether it be a relationship (work, sexual, or both); professionally; or what is known in criminal psychology as “familiar strangers; those we see every day, such as on a regular basis, but know little about them (the clerk at your convenience store, the conductor on the train that takes your ticket, the barista behind the counter of your favorite java joint, etc.)

Serial killers love to prowl at night for their victim selection. It’s quite simple why – there are usually less people around to witness their actions, and the cover of darkness also helps out quite well. That is why certain victims are prime candidates to fall prey to them.

Late night waitresses/waiters. Convenience store clerks. Delivery persons who operate in the wee hours, such as bread, or milk, or newspapers or cake. Nurses. Doctors. Police officers. Almost anyone who works late. As well as other offenders. Prostitutes. Burglars. Then there are the really helpless. The homeless. Runaways. And on. However, there are many more reasons these offenders operate in the evening, which will be the subject of a future post.

Burglaries, for example, have different sets of criteria for the criminal. Burglaries take many forms. The police, to effectively catch these criminals must understand the type of burglary, the characteristics of the offense, and the demographics of the victims. For example, burglaries of middle-class or poor residences are more likely to be committed by juveniles, or young adults, and that probability increases in cases where entry is through a broken window, or when the search for property appears scattered or haphazard. Hotel burglaries, on the other hand, are more likely to be committed by older, experienced burglars.

In residential burglaries, the method of entry and exit, as well as the type of search, will provide information about the suspect. A real life example: more experienced burglars, once inside a home, will frequently unlock all the doors, sometimes even all the windows in order to get out quickly should the owner return. The more professional burglar empties all the dresser draws on a bed, then sifts through. Some only specify wealthy homes. As an experienced burglar once told me “You’ll do the same time in jail whether you do a big job, or a small job, so go for the biggest you can do.”

Senior citizens are rarely burglarized, as the criminal knows they often have few material possessions of value. A senior citizen’s assets lie mostly in savings, bonds, stocks, etc. That is why seniors are selected for economic or white collar schemes, such as being ripped off by contractors who either never show up to do the work, Ponzi schemes, the “overseas lover” where they target divorced seniors, telemarketing scams, and so on. This is a prime example of criminals carefully selecting their targets. Elderly may be ripped off by a personal theft, such as a senior getting his/her wallet snatched, but very rarely a home burglary.

So, as we have seen, the victim selection process is one honed by the criminal after being field tested. And you are the human subjects. That is why when you create characters, whether they be the criminal or a victim, always remember this:

ALL criminals need THREE things to commit ANY crime:

1. They know that committing the crime may get them incarcerated, but they make a conscious decision to take that risk.

2. After they have decided that the risk is worth it, then they have to justify that what they are about to do is morally wrong. When they can overcome this, they then move on to number three . . .

3. An available victim. Without anyone available, they can’t commit the crime. In a material theft, not being able to open the car door to steal that Corvette, or in a burglary not being able to open the door to a residence to burglarize it.

So, in your works, maybe have the suspect ponder, or dwell, or maybe even wrestle with any of the first two areas. Good versus evil. Bad versus good. It’s good psychological fodder.

Just don’t steal that poor old lady’s parking spot in the process . . .