Fingerprints. Blood Spatter. Bullets left at a crime scene. A hair found on the victim. A surveillance video of the suspect entering the victim’s home.

Aaahhh . . . don’t you just love those crime television shows! A plethora of evidence left behind for the actors to muddle over and eventually use to snag a suspect. I mean, how else can they solve the crime in 60 minutes?

But what happens when police encounter none of this evidence, for example, at a murder victim’s home, the apparent crime scene? No fingerprints are found on tables, glass, etc. other than the victim’s. No unknown hairs left on the victim’s clothing. No bullets left behind, because the victim wasn’t shot. No blood spatter, because the victim wasn’t beaten. No surveillance video. Nothing. Nada. Zilch. Impossible you say . . . there HAS to be evidence somewhere, just like the last episode of Criminal Minds you saw last week.

Let’s go back to TV land, whether it be mainstream or Netflix. What would happen if teams of detectives found no forensic evidence at a crime scene. They have nothing to go on. Imagine the show’s description as you scroll through whether to watch the new episode tonight . . . “Detectives Smith & Jones find a local businessman murdered at his home, but since they couldn’t find any forensic evidence, they discuss their summer vacations.” Hmmm . . . maybe it’s time to scroll and find those old Little House on the Prairie reruns.

The REAL DEAL is that many, many times, crimes are committed and no forensic evidence is found at the scene. There are several reasons this could happen. One is the “crime scene” isn’t where the crime actually occurred, just where the body was found (referred to as the secondary crime scene), so all the hairs, blood spatter, etc. would most likely be found at the site of the original (primary) crime scene. Another reason may be that the scene is the primary one, but the suspects spent time cleaning up the scene. A third reason may be poor crime scene investigation, where the evidence IS there, but is not detected (possible inexperienced investigators or sloppy procedures).

Here’s an example . . . Harry H. Harold is a well known businessman in New York City. He is found tied up, bound and dead in his luxury apartment overlooking Central Park West. The autopsy reveals he had been choked to death by hand (manual strangulation). The crime scene search reveals no forced entry into his apartment. No hairs on his clothing. No fingerprints other than his own in the home. No blood spatter. Nothing. Why? Because H.H.H. was really killed at the home of his business partner, then tied, bound and brought to his apartment, with the killer opening the door with H.H.H.’s own key. So, his apartment is the secondary scene, not the primary.

How would YOU solve this crime? I’m sure you’d realize that you would first need to figure out who would want to kill H.H.H., because behind every killing is a motive, although that motive may not be first apparent. So, three weeks later, eventually you find yourself at the doorstep of his business partner, Gill T. Azhell, armed with a search warrant to do a thorough search for evidence. There’s only one problem: your suspect had three weeks to clean his home, knowing the police may come a’ knocking. But, you KNOW he did it! Your 3 week investigation showed he was skimming money from the business to pay for his girlfriend’s condo, new Mercedes and vacations in Turks & Caicos without his wife finding out. He HAD to do it! He HAD the motive. He HAD the opportunity! But, you have no evidence.

Hmm. What would Charles Ingalls do?

He would need to interview and interrogate Gill T. Azhell to see if he could obtain some incriminating admissions.

So Charles interviews the suspect for three hours, gives him some coffee, and even dangles some of Caroline’s famous apple fritters under his nose, but no luck. No confession. No admission. Nada.

This scenario (minus Charles and the apple fritters) happens quite frequently in real criminal investigations, but is usually never shown in TV land because it would be boring as hell. Would you watch a crime show where the detectives never solve anything? Imagine tuning in to the Pioneer Woman and she tells you she that she forgot to go food shopping so she can’t make anything. You get the picture.

There is one thing left in a great investigators bag of tricks.

And it never expires. It never grows old. It works on any suspect, tall or short, male or female, rich or poor.

The suspect’s own words.

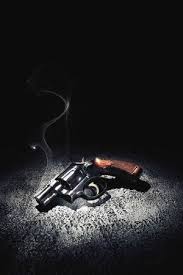

The science of analyzing a suspect’s own words during an interview and interrogation (more about the difference later) is called word or statement analysis. It is the science of studying what a suspect says about certain aspects of the crime, his or her life, daily routines, even how they feel about the crime. But it is not a “smoking gun”, simply a tool to get you to the evidence, or maybe even a confession.

But be warned . . . confessions aren’t worth too much. A good defense attorney will get the confession thrown out of court, which will cause the evidence found as a result of that confession to also be thrown out (see my post on “fruit of the poisonous tree), due to improper Miranda warnings, or the suspect was withheld food, water, medication, or Caroline Ingall’s apple fritters during the interview/interrogation.

However, a great investigator, armed with the science of word/statement analysis, can use the suspect’s own words against them. The investigator can determine if the suspect is lying. If the suspect is fabricating a false rendition of the events the day of the crime. If the suspect is not being truthful about his relationship with the victim. If the suspect had an accomplice. If the suspect was involved in the crime. If the suspect was the murderer. The list is endless.

I’ll tell you how a suspect uses “stall tactics.” How suspects “minimize” the crime. How great investigators do the same – but for a completely different reason. Why investigators “maximize” the crime to the suspect. How a suspect should be interviewed, both physically and emotionally. Where a suspect should NEVER EVER be interviewed by experienced investigators, and why. And tons more examples, all based on my real cases.

That’s right . . . the complete scoop in Part Two of this post. All this so you can be a better writer, director, producer, or actor.

So in the meantime, I’ll make the coffee,

you whip up the apple fritters . . .