In my previous posts on evidence, I covered the definition of the term, as well as the two different types. Now it’s time to get down on our hands and knees to find some evidence using what is called “ambient” lighting techniques (that means just what your eyes can see unassisted without additional lights), or “oblique” lighting, (such as a flashlight, cell phone light, spotlight, etc.)

Many times, you will read an article about a crime, and the reporter will note that no evidence was found at the crime scene. That doesn’t mean there wasn’t any evidence; it just means that the evidence wasn’t found.

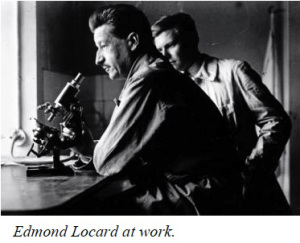

The most famous exchange principle of evidence is by Sir Edmond Locard. To summarize it: when two objects come together and meet, there is always an exchange of evidence.

I previously covered that evidence comes in two types: real/physical and testimonial. Now, I will break the real/testimonial into two classic distinctions. You must know this if you are a serious writer – and serious writers get the facts correct. I am presuming you are – otherwise you wouldn’t be reading this and instead would be sitting on the sofa in your favorite sweatpants watching SpongeBob.

The distinction I am about to talk about between the two types of real/physical evidence is so important that many a person has been convicted – perhaps rightfully, or perhaps wrongly, and been incarcerated or acquitted based on what was found at the crime scene.

The two types: evidence with “individual” characteristics, and evidence with “class” characteristics.

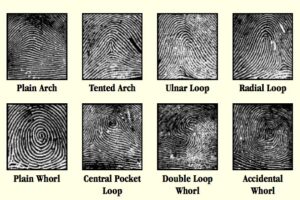

Individual characteristics means that the evidence can be POSITIVELY identified as having come from a specific source or person, if it has sufficient identifying characteristics. Some examples of evidence with individual characteristics are fingerprints, bullets, shoeprints, broken pieces of glass, ripped pieces of tape, paper, etc., tool marks, bite marks, tire impressions in dirt and mud, and also blood.

In other words, a direct comparison can be matched.

Broken items, such as glass, paper, tape, etc. can be microscopically matched to put the ripped edges from one found at a crime scene to the other piece found on the suspect or at his home, car, place of work, etc. For example, a bank robber uses a ripped piece of paper to write his note on that he passes to the teller, and the other half of the ripped piece is found in his desk at home. The two pieces can be matched together. The same holds true for tape, such as duct tape used in binding; or glass broken during a home invasion. However, and this is very important, items that are cut, such as with a scissor or razor, can’t be matched as the cut is too straight and without enough unique jagged and ripped edges to make a positive match.

Class characteristics means that the evidence, no matter how thoroughly examined, can only be categorized into a class. A positive match, such as in evidence with individual characteristics, can never be done, because there is a possibility of more than one source for the evidence found. It’s like entering a contest to win a new car where there are only three top prizes, and you came in fourth. Congratulations – you and three million other people won a keychain. Woo-hoo!

Some examples of class characteristics evidence are soil, hairs, fibers, glass fragments too small to be matched, cut pieces of paper or tape, shoe prints, rope, fibers, shoe impressions, tire prints or tire impressions with no detail in the sole or treads, or bullets or tool marks with no real detail.

In other words, a direct comparison cannot be matched.

Here’s a real life example: I had been to a homicide scene where a woman was apparently strangled in her home. Under oblique lighting techniques, she was found to have reddish fibers round her neck. The prime suspect in the case was her boss, with whom she was having an affair. A red scarf was found in her home. A search of the suspect’s vehicle recovered reddish fibers on his front seats and steering wheel, and also on his sweater. The fibers from the crime scene and from the suspect were sent for forensic comparison at a lab, where it was determined they were of a similar material (wool), a similar dye color (red), a similar density, and a similar twist (six strands). It could never be determined they came from the victim’s scarf.

Positively matched?

No.

Circumstantially matched?

Yes.

Although in forensic investigations it is desirable to have all evidence of the “individual” characteristics traits, class characteristic evidence is better than no evidence. In cases where there is only class characteristic evidence found, it is better to have an overwhelming amount of it, making it harder for the suspect to refute.

So, you just brought some murderous mayhem to a character in your work that surely deserved it. The deed has been done. All that’s left is for you to decide what you want left behind.

Think about what type of evidence would help draw out the tension and suspense if found at your crime scene.

Should the ransom note be cut . . . or ripped?

Should the suspect leave fingerprints on the windowsill . . . or fibers from his shirt?

Isn’t it amazing what power you have as a writer to control what is or isn’t found at your crime scene!

So, grab a cup of your favorite beverage and get writing.

Just make sure that while you are on your hands and knees at your fictitious crime scene you don’t leave your cheap keychain behind.

To your success!