So, you have been working on your Great American Novel . . . whether it is mystery, romance, suspense, historical, or anything in between, wherever there is love – there is hate, jealousy, and greed. And you’ve been toying with the idea of one of your characters getting, well . . . you know . . . on the wrong side of a pistol. Maybe you’re not that familiar with firearms, projectiles, and the wounds they produce, so you hesitate to write it.

Very often, the questions I get asked by writers at my forensic science presentation “Whodunit: 101 Mistakes Mystery Writers Make” is what does a real gunshot wound look like? Is it as bloody as on television? What about the difference between someone being shot in the head versus the leg? How can a police officer tell whether the bullet went in the chest or the person was shot in the back and the bullet came out the chest? What do police do to compare projectiles from a suspect’s gun to the crime scene?

It’s only normal that writers ask these questions, because you really can’t do trial and error on yourself. At least, you shouldn’t. Now, you may see wounds on television, but remember these are the same people that bring you SpongeBob and Sesame Street.

Perhaps you know a doctor or nurse that works in the emergency room. The only problem there is that they have not gone to the crime scene, so they can’t recreate the scene and determine, along with other crucial evidence, such as blood spatter, how the bullet entered the body.

Here in this post we will cover the nomenclature for firearms, the types of firearms there are, the projectiles used in them (you’re not using the word “bullet” in your works, are you? Bullet is an incorrect term!) and the wounds these projectiles make. Unfortunately, it’s a fact that in our society firearms account for the overwhelming amount of homicides.

The forensic science term for the study and analysis of firearms and projectiles is known as “ballistics.” There is so much to cover, I will have many posts continuing on this area. It is a fascinating one, and once you understand all the aspects will be more confident in using it in your writings. Ballistics is a very scientific and specialized field of forensic science; your attention to detail will pay off.

For you to set up a scene in your work where a firearm is used, you better be accurate in the weapon, projectiles used, and the wounds that arise out of the shooting. Remember, poor facts = poor writing. Garbage in, garbage out as they say in police work.

A little secret I will tell you later on is that firearms themselves can make wounds to the body, not just the projectiles fired out of them.

Try learning THAT on television.

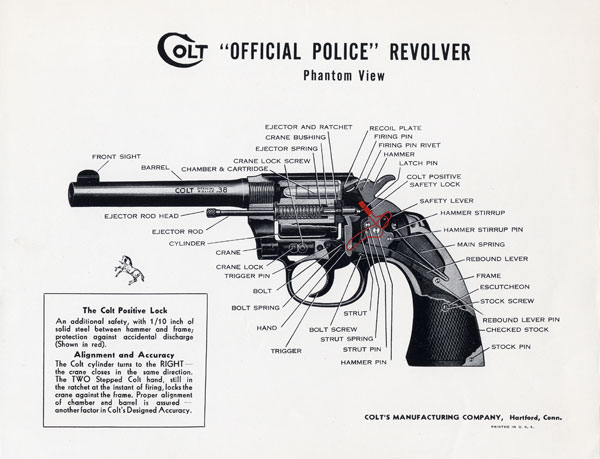

Firearms have two actions types, double action and single action. A double action firearm is the type where the trigger is pulled, it cocks the hammer back until pulled to a certain point, then releases it to strike the firing pin. This double action type firearm involves a heavier “trigger pull,” a term I will cover. The double action type is very common, used on both revolvers and automatic firearms.

A single action firearm works by having the hammer manually cocked back by the user’s thumb, or by pulling the slide back on an automatic. This type of firearm involves less trigger pull, and its design is used on both revolvers and automatic firearms. Below is a diagram of a revolver.

In a revolver, the projectiles are loaded into a revolving cylinder holding either five or six “rounds,” also known as projectiles. The amount is simply a matter of choice from each manufacturer. As the trigger is pulled, the cylinder revolves, moving the round into position for the hammer to move forward and thus have the firing pins strike the bottom of the projectile. Again, depending on the manufacturer, some revolvers have cylinders that revolve clockwise, some revolve counter-clockwise. In a revolver, once it is fired, and a projectile discharged, the cartridge, or base as it is also called of the projectile remains in the cylinder until manually ejected by the user. Below is a diagram of an automatic.

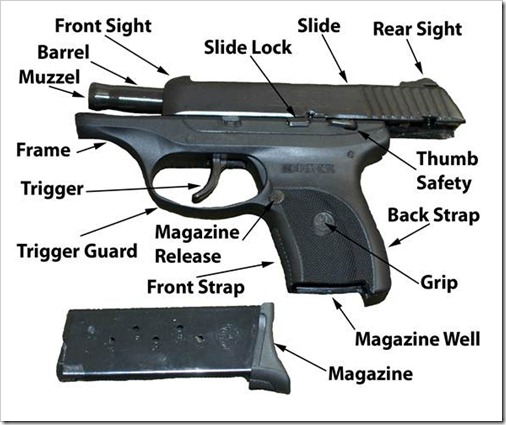

In an automatic firearm, the projectiles are loaded into a “magazine.” The magazine has a tight spring and can hold as little or as many projectiles as each manufacturer produces. Now, some misinformed and mislead writers call the magazine a “clip.” Wrong, my dear Watson. Stop watching the telly for your forensic information.

The magazine, once loaded, is then inserted up into the magazine well where the projectile, under spring loaded pressure from the magazine, is ready to be used. In an automatic, once it is fired, and a projectile discharged, the cartridge automatically ejects, usually to the shooter’s right.

The firearm must be manually “loaded” by sliding the slide forward which lines up the projectile to be fired. After each shot, the firearm automatically reloads the next projectile into the ready area awaiting the next pull of the trigger. Just like a revolver, the hammer must slam forward, causing the firing pin to strike the base of the cartridge.

How does the projectile fire out of the gun? Looking at the picture, a projectile has some small sensitive explosive powder, called “primer” in the base. Right above that is the explosive powdered “gunpowder,” and above that is the tip of the projectile, called the “bullet.” The bullet is usually made of lead or lead jacketed with a harder metal.

Once the primer is struck by the firing pin, the pin causes the primer to ignite, that then causes the gunpowder to ignite causing great amounts of gas, which then causes the projectile to move down the barrel and ultimately out of the firearm. The expanding gases push the bullet down and out the barrel.

A very important point to know is that if all this happens, then the firing pin leaves a small “dimple” in the bottom of the cartridge. Why is that important? I’m glad you asked, but I have to keep you hanging for now! Sorry, but I promise you I will tell you.

The barrels of firearms are produced on machines, and as such even with polishing, have imperfections. It is these imperfections that leave marks on the bullets that if found at the crime scene, or in the body of the victim, can later be compared and sometimes matched up. It is this matching that puts the firearm found on a suspect as the one used in the crime, and when matched, is a home run for the police and forensic investigator.

In the posts that will follow, I will cover so much more on the important area of ballistics in forensic science, and you will learn what exactly are lands, grooves, contact wounds, close contact wounds, blowback, near contact wounds, stovepipes, stippling, gunshot residue, shotguns, wadding, shotgun buck, different types of projectiles, entrance wounds, exit wounds, trigger pull, rifling, how suspect firearms are test-fired, and much, much more.

In the upcoming Premium Membership Area, I will post many videos, all packed with actual pictures of not only ballistics, but many different topics so you can see exactly what I am talking about. The best is yet to come.