So, let’s move on to the actual crime scene. Perhaps you are at the point in your work where you need a little murder and mayhem. Someone’s going to get what they deserve. The rotten little scum. Of course, this is an excellent avenue to throw a red herring to your readers. You always want your readers to TRY to figure out what happened. When of course, you know what HAS happened. And what WILL happen.

Whether you want to have the sneaky husband poisoned, or the perverted neighbor stabbed, or maybe the annoying stalking co-worker of your heroine found floating face down in his community pool, the time has come for you to set the wheels in motion. Now, the deed has been done – you’ve penned the mayhem. What next?

In reality, the police and subsequent crime scene investigators will respond. It is crucial that in your setting, you know exactly what agency will respond. For example, in Florida, the Sheriff’s Department will respond to crime scenes, assisting smaller jurisdictions. In New York City, there is a separate crime scene unit, but it is part of the NYPD.

Perhaps your setting is a small town. They may not have anyone trained in forensics, so they contact the Sheriff’s Department to do the work for them. However, territorial disputes are quite often in law enforcement, and the local town may send their slightly trained but not quite expert officer because they don’t want to be outshined by the larger agency.

Many small jurisdictions will contact the larger agency and work quite well side by side. But not all. This is a great avenue to pursue in your work. It builds tension. Animosity. Back stabbing. Ah, the good old days, how I miss them! All that tension and animosity and back stabbing is good for you as a writer. Why? Because tension, animosity and back stabbing causes mistakes to happen. Evidence to be overlooked. Procedures not followed correctly. You get the picture.

As a writer, this is your golden opportunity, at the time when a crime scene is being “processed” as it is called, to create mistakes. It allows your characters to be human, as we all are. The mistakes made by your forensic investigator or detective can greatly affect the investigation, and as long as these mistakes are brought out later by you, the creator of these mistakes, your readers will have more credibility for you. But, you MUST reveal the mistakes somewhere in your work. If you don’t, they will think that you made the forensic investigator or detective follow a procedure that they KNOW is incorrect. The readers will then assume that you do not know what you are writing about. They’ll reward you by either stop reading your work, or never read you again. You’ll have the credibility of zero. Zilch. Nada.

Here’s the meat on the bone for what exactly a crime scene investigator should follow when processing a crime scene. Knowing the correct procedure, and what should be done, allows you to create the twist in your work for what wasn’t done, or done incorrectly.

The first step in processing a crime scene is to video record the scene. Properly done, it is the correct procedure to do so like a funnel. The videographer first records the overall general scene, like in the opening of a funnel, wide. Then they progress towards the actual scene, with the last area video recording being, let’s say in the case of a homicide, the body.

Pretend for example your work has the philandering husband found dead in the master bedroom of the secret apartment he has near his job, which he keeps just for his naughty trysts. The correct way to video record this crime scene is to do outside video of the building, then the entry/exit points, then the elevator, then the floor his apartment was on, then the front door to the apartment, then the first rooms once entering, then all the rooms, then lastly the room he is in, ending with extensive video of the body. That is the funnel effect-you go from wide to narrow, with the most important piece of evidence, the body, last. During this entire video the sound should be off. This way, there are no external comments or distractions.

After the video is completed, still photography should be done, again following the funnel effect.

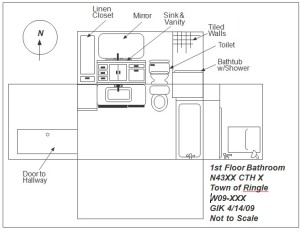

Thirdly, a sketch should be performed. The one done at the scene is a “rough” one, where the dimensions are exact, but the sketch is rudimentary. A sketch should be of the “overhead” or “bird’s eye view” type, not three dimensional. The sketch is then redone at a later date, based on the details of the rough sketch, into a “final” sketch. This can be done free hand, or with a CAD also known as a Computer Assisted Diagram, where there are little templates of chairs, tables, etc. to point and drag into the sketch. The sketch must have the creator’s name, date, location, as well as the direction of North clearly noted. The sketch also must be noted as “not to scale” so that perspective, if incorrect, will not affect the credibility of the sketch. A sketch adds a different dimension that photos and video cannot. Thus, video, photos and sketching compliment each other.

After all this is done, and ONLY after this is done, does the actual “processing” of the scene occur. The most fragile of evidence is processed first. If it is an outdoor scene, special care must be used as to what may be damaged by approaching rain, snow, wind, etc. Fingerprints and blood are the two most fragile types of evidence, so forensic investigators try to process them first, as they degrade or may be destroyed easily and quickly.

So, remember the correct order for crime scene processing: video, then still photography, then sketching, then processing.

As a writer, this is a gold mine of opportunity to create a forensic boo boo, and I don’t mean a Honey Boo Boo. The alcoholic detective photographs the scene, but loses the memory card. The lazy forensic investigator fudges the dimensions of the sketch, because he is in a hurry to get home for his favorite team’s football game. Now you’re thinking! Real people making real mistakes.

Remember, as long as you make amends with your readers and have the mistake come out, they won’t think that you did your forensic research watching Honey Boo Boo. They’ll know your got the real deal scoop right HERE. Remember, my posts are not based on what I have read, or what I have seen on television, or what I overheard at a mystery writers convention – but on actual crime scenes I have processed.

In my next post in this series, we will get much more specific on the handling, collection and preservation of evidence. How evidence should be packaged. How it should be transported. Here’s a little homework for you. Should wet evidence, like a bloody sock, be packaged and transported in a paper or a plastic evidence bag? Hmm. The answer next post.

Be sure to read my other posts on evidence and crime scenes to greater familiarize yourself with them and you’ll be ready to jump headfirst into introducing some crime scene chaos in your work.

Now, let’s break out the Pinot and celebrate your future success.